It’s not always a case of debt = bad. Used intelligently, technical debt provides quick fixes to problems and boosts innovation. However, you’ll soon know when your tech debt’s not serving you well. Below: three signs your tech debt needs paying off.

Understanding tech debt — beware the buzzword

Technical debt is an overused term, often used to indicate ‘bad code’ or ‘work we don’t approve of’. Towards and Understanding of Technical Debt by Kellan Elliot McCrea, 2016, sheds light on how technical debt looks in practice. Leaning on the concept that ‘all code is a liability’ McCrea pinpoints five distinct aspects of how ‘tech debt’ manifests itself.

- Maintenance work

- Features of the codebase that resist change

- Operability choices that resist change

- Code choices that suck the will to live

- Dependencies that resist upgrading

De-demonizing technical debt

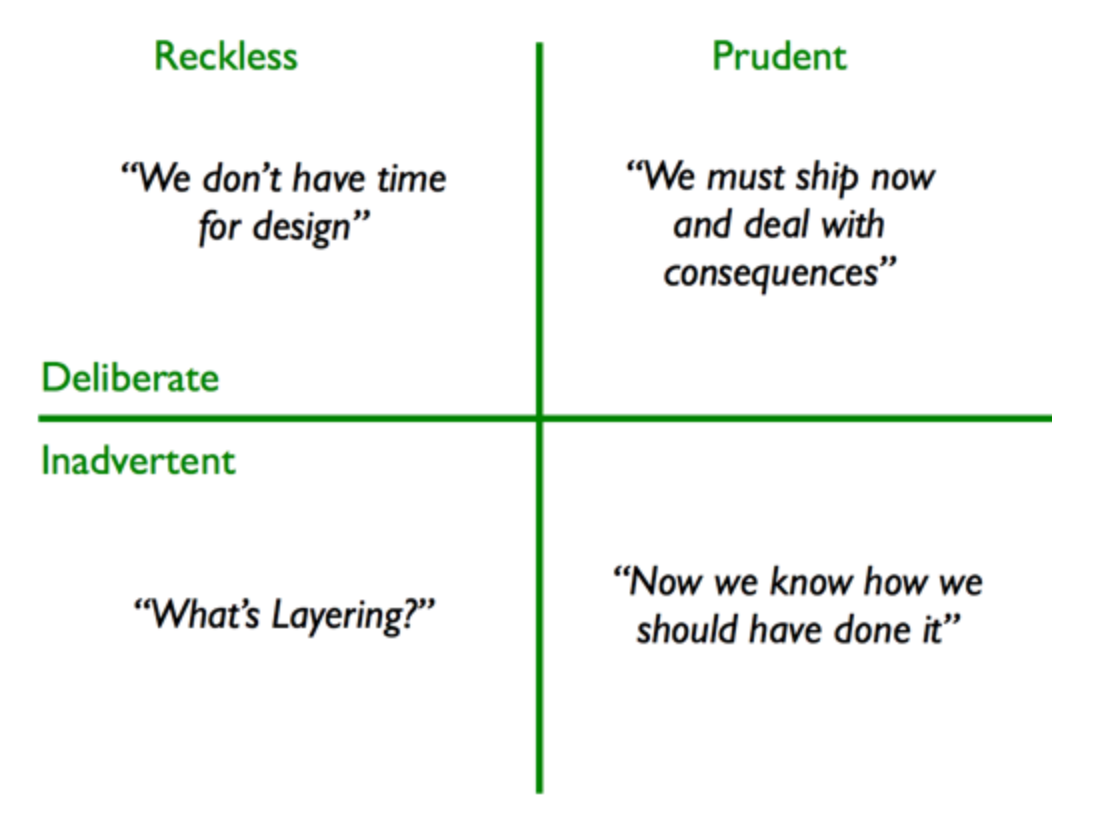

Taken in isolation, none of the above are going to topple your business. In tech and elsewhere, debt means the decision to realize something now and pay later, when resources allow. Martin Fowler, co-signatory of the Agile Manifesto, divides technical debt into prudent and reckless debt.

The good, the bad, and the reckless

Some varieties of tech debt have little or nothing to recommend it. Reckless technical debt tends to be reactive — gaffa tape to fix escalating problems — with no preemptive, future-facing awareness of how to fix in future.

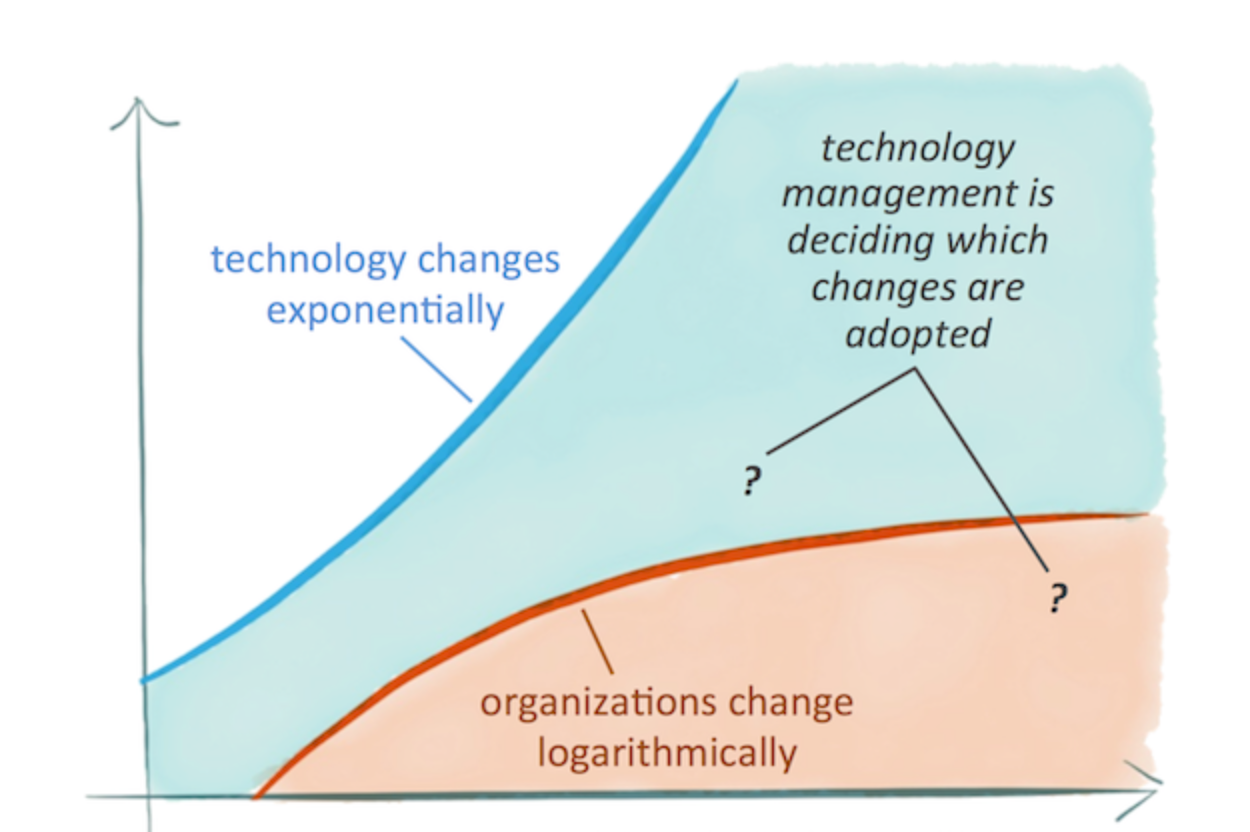

Martec’s law famously shows how technology changes exponentially whereas organizations change logarithmically. Lack of outward-facing awareness is often the reason behind the ‘stack mentality’ variety of tech debt. Step forward legacy banks or NHS Scotland. If an engineering team has taken a wrong punt on the usefulness of a system or piece of code in future, or if they become attached to certain ways of working, it can be hard for them to let go until it is too late. Given the curvature of the graph representing Martec’s law (see graph below), if you decide to maintain in-house systems a serious consideration is how to prevent engineering teams becoming blinkered and losing sight of what’s ahead.

Intelligently used, technical debt helps with engineering agility. It might mean a considered decision to settle with a second-rate design pattern — temporarily — in order to get a product to market sooner, to quickly fix an obstacle standing in the way of business goals, or just to focus on getting things done, focusing on creative solutions over the elusive goal of perfection. Using technical debt prudently means being conscious of when, how and what resources are needed to tidy up any messiness that might have occurred as part of the process.

Here, the biggest insurance against the dark side of technical debt is to identify signs that prudent technical debt is starting to shift into the reckless category.

Tech debt red alerts

Knowing when tech debt needs fixing is half the battle. On an organizational level there are three scenarios when hacked and/or home-built solutions might start to get shaky more quickly. As more than one of these scenarios starts to play out, so the bias leans more heavily towards buying a service over building your own. However this is not to say off-the-shelf solutions are the only way forward — each case is different.

Three signs existing tech debt might soon cause problems:

1. Your operations are scaling

- Signs: Standard signs of positive growth — sudden spikes in traffic, demand, users. As bigger clients use your product the words ‘mission-critical’ carry more weight. System failure has more at stake.

- Debt red alerts: Standard indications of system failure, more developer hours seem to be dedicated to ‘fire-fighting’ than innovation and/ or product development.

- Remedies: Expand your engineering resource and think carefully how their time is spent. Received wisdom says off-the-shelf solutions, having anticipated glitches that come as part of running a service at scale, and developed features to solve these, are a good idea. But when choosing a product it’s worth reverse engineering features back into tech requirements. This helps identify unknown requirements and recognize what you need so you can choose the right product for you and/ or intelligently refocus your engineering team’s goals.

2. Your tech is diversifying

- Signs: While your developer team is concentrating on its function, different tech stacks emerge and become a more prevalent part of the system.

- Debt red alerts: Engineers start spending a lot of time building translation layers and unnatural interfaces so new and old systems can communicate and keep operating. Unexpected connection issues become a frequent occurrence. Spending time extending software that was never meant to service other layers.

- Remedies: It depends. Continuing to build on layers suitable for just one part of the stack is a sure fire way to incur more debt. One way forward lies in stricter management — agreeing a set of default languages and protocols for your organization, bearing in mind this too could become a limiting factor if new innovations need systems. Equally, the option to start afresh with a new service layer (buy) should be taken seriously if the self-built solution is not compatible with other layers. Here any solution without built-in interoperability is short-termist. While it might promise to rid you of technical debt short-term, single-protocol solutions come at the cost of vendor lock-in, meaning you will incur more debt when other stacks come to the fore. If there’s a chance you’ll once again be left building translation layers, it’s better to buy a layer with built-in interoperability.

3. Your system architecture is becoming more loosely-coupled

- Signs: Sometimes known as inverse Conway’s law, loosely-coupled systems occur when developer teams cluster around available technology. The organization finds itself with a larger number of separate services clusters.

- Debt red alerts: Tunnel vision — teams stop communicating, innovations aren’t joined up

- Remedies: Once again, interoperability is an important consideration here — as it enables separate teams to better integrate the technology they are working on.

Take back control

Far from being something to avoid at all costs, technical debt is something to be actively and intelligently managed.

Three ways to take control of tech debt:

- Recognize when tech debt is about to come back and bite. Proactively predict when debt will cease to be ‘prudent’ and start to cause problems (both within your team and outside), and implement mechanisms in advance to mitigate.

- Recognize when done is better than perfect. Don’t over optimize your solution to the extent you stifle creativity or fail to solve immediate problems , but equally don’t take shortcuts that you know will be problems as you scale, when you arguably have the least time to dedicate to the solution. These bad decisions can linger for years to come.

- Remember the ‘all code is debt’ adage. Maintaining engineering teams who in turn maintain code is a costly business. The less code you have to manage, the less it costs in people hours. The traditional argument says bought solutions to tech debt are good because buying has a fixed predictable cost, and building comes with unknown and guaranteed costs in the future. However, it’s important to consider how bought solutions interplay with other elements in your system, and whether this particular part of your stack is a business priority at the present time.